In high risk industries, overconfidence regarding our understanding of what to do when disasters occur can be fatal. A series of simulations we ran at the Diggers & Dealers mining conference in Australia in August this year revealed what many in the mining industry already know, that despite improvements in safety compliance over the past several decades, many workers remain overconfident about their safety knowledge, and remain unprepared for unexpected, anomalous events.

While last month's article covered some of the root causes of this human error, we address here how to build programs that counteract this human error. In other words, how do we design more effective safety programs that can neutralise the source of these adverse tendencies?

A simple experiment

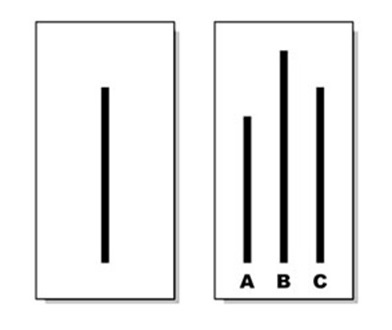

Examine the figure below. Which one of the lines in the box on the right is the same length as the line in the box on the left?

This is a seemingly easy and obvious task for anyone who has normal vision. If you selected ‘C', you are correct. However, under specific experimental conditions, 32% of people will select either ‘A' or ‘B'. Why? What would drive people to choose an answer that is so clearly incorrect?

In this classic experiment in social psychology from the 1950s, Solomon Asch put eight people in a room together and showed them these images. Each person was asked to state, one by one, which line length on the right matched the line on the left. But here is the trick: only one person in the room was a naïve participant, while the other seven people were hired as part of the experiment. Each of the seven participants that were in on the study agreed beforehand on an incorrect answer and one by one they gave the same incorrect answer. The naïve participant answered last. In 32% of the cases, the naïve participant went along with what the other seven participants had said.

Asch repeated this experiment with added questions. The participants were asked to make several different judgments with equally obvious answers. Asch found that 75% of participants gave the incorrect answer at least once - that is, they conformed to the group's response on at least one of several similar tasks. Twenty-five per cent were never swayed by the group. But 5% were swayed by the group on all of the incorrect answers.

Most importantly, after the experiment was over, participants were asked why they chose the wrong answer. Most of them explained that they were giving the wrong answer just to go along with the group, even though they knew the right one. But a sizeable minority truly believed that the groups' answer was correct, which leads to the conclusion that their actual perception of the lines had been altered by the opinions of others. This experiment has been reproduced many times over the years, and provides one of the most powerful illustrations of the enormous influence a group has to shape an individual's behaviour.

We are highly attuned to social cues that override our individual opinions, beliefs and behaviours. Asch's study is just one among hundreds of studies demonstrating that our opinions are more easily swayed by our social group than by direct evidence, information or individual evaluations. This is vividly illustrated by the rise of the social media like Facebook and its ability to influence opinion and belief over traditional media sources.

Our decision making is largely based on the behaviour of the groups we belong to, not our individual rational assessments or our individual failures and shortcomings. More recently, some researchers have argued that very idea of individual intelligence may not exist at all. As a species, our evolutionary advantage is not our individual rationality, but our ability to think as a group. What allows us to build cities while other animals do not isn't our individual brain power, it is our ability to think and act in complex coordinated activities with others.

What does this have to do with safe behaviour in a mining context? Every mining company has the goal of zero fatalities and zero lost-time injuries, and all of them know that they need to continuously work against unsafe behaviours and bad habits that can lead to adverse behaviours. But one of the most prevalent mistakes of behaviour change efforts is a tendency to attribute error to the individual. When we locate a failure of intelligence at the individual level, we tend to try to generate a solution at the individual level. We compile cases to see what exactly went wrong, locating the specific sources of human error. We deliver new safety instructions to raise awareness and fill in the worker's gaps in knowledge. We design new training to help correct for the individual's bad habits. But many of these individual-level interventions miss something fundamental about the nature of human intelligence: we do not think alone.

Intelligence tests, performance evaluations and capabilities assessments all show us how well individuals do on measures of general intelligence or on specific skill sets. These tools are good at predicting success for tasks dependent on individual skills, like playing chess or competing on Jeopardy. But this kind of intelligence is almost never sufficient in the real world, where people are always acting with teams, within larger organizational contexts.

In fact, studies on high performing teams across a variety of tasks repeatedly demonstrate that the team with the highest collection of intelligent individuals are almost never the most successful. Strong leadership also doesn't correlate with high performance. Instead, the qualities most likely to predict winners are, 1) teams that allow equal time for team members to share and critique interpretations, and 2) heightened sensitivity to the thoughts, feelings and behaviours of others. By strengthening the connective properties of group members, this research shows that the best performing teams are able to harness the dynamic of the group over the individuals and use it to their advantage.

While the group's influence can be used to enhance performance, it also exacerbates the risks. The Asch experiment detailed above showed high levels of conformity to group pressure for erroneous responses on a task where the answer is measurable and relatively clear. Now imagine what happens when the conditions are more ambiguous, when judgment is impaired by panic and uncertainty, and when individuals have more doubt about their ability to assess the best course of action. Under ambiguous conditions, the habits of the group and the cultural norms exert a much larger influence over how the individual behaves.

Furthermore, the group norms and social pressures don't have to be explicit. Unconscious patterns outside of our awareness shape the group's unquestioned norms. We need to be asking ourselves: what bad habits, gaps and systemic oversights exist among our teams? In the organisation? In the mining industry as a whole? Do our programs and procedures have unquestioned deficiencies that influence unsafe behaviours at the individual level? Are we, as an industry, overconfident about our safety preparedness? Based on our findings at Diggers and Dealers, the answer is yes.

Safety training programs that favour fact retention among individuals over learning the fundamental principles behind safety awareness as a team are prevalent. They favour the ability to comply with protocol over the ability to dynamically respond as a team to complicated scenarios. And they assess the performance of individuals in safety adherence, rather than scrutinizing the gaps in team skill sets or the systemic weaknesses in the safety culture of practice. These learning and training paradigms that emphasize individual safety awareness and human error reinforce erroneous (and ultimately dangerous) assumptions about the nature of intelligence and decision making.

To understand an individual's behaviour in the real world, we must move beyond individual level performance evaluations. More effective assessments would evaluate how the individual contributes to a group's success, how the team functions as a unit, and, most importantly, how the larger culture of practice shapes individual behaviour and promotes or diminishes the likelihood of error. Even when the error seems to have an individual-level cause, these kinds of assessments capture the subtler aspects of the systemic causes of failure.

The safest and most effective teams underground avoid attributing errors to "bad apples" and individual mistakes. High performing organizations have three critical attributes:

1) They have high standards and vetting systems that evaluate an individual's risk and contribution to the functioning of the organization and the team.

2) They ensure that all team members are accountable for any individual behaviours.

3) They enforce corrective measures among teams in which members are encouraged to be critical when they see unsafe behaviour and are critical of procedures and protocol that may lead to incidents.

Most importantly, overcoming human error at the individual level begins with an understanding that individual behaviour is largely a function of the social dynamic of a group guided by the organisational culture of practice.

Most safety incidents in the mining industry occur in situations of high ambiguity and uncertainty. Under these conditions, individual team members rely even more heavily on the intelligence of the team as a unit to solve problems and act effectively.

As individuals, we will always be exposed to some limitation in our expertise, we will fall prey to overconfidence and be blinded by deficits in our capacity to make sound judgments, especially under stressful conditions. But while these limitations are an inevitable feature of our individual decision-making, it does not mean that disasters, injuries and fatalities are an inevitable feature of our operating environments. Our ability to overcome these deficits is measured by the degree to which we are willing to examine, transform and exploit the power of our collective intelligence.

*Eddy Solbrandt is principal of GPR Dehler, a 30-year-old London-based consultancy that has worked with large mining houses since 2008 on the application of immersive learning tools and methods