Kabanga's time has come. Not simply because it is the world's largest development-ready nickel sulphide and cobalt deposit, but also because of two technology events: a unique metal refining system; and the electric vehicle revolution.

Discovered almost 50 years ago in the northwest corner of Tanzania, Kabanga has been the subject of repeated exploration programmes and feasibility studies by some of the world's leading mining companies.

Anglo American, BHP, Glencore and Barrick invested hundreds of millions of dollars in drilling and project analysis.

But the big miners could never overcome Kabanga's remote location, a wildly fluctuating nickel price, and a rigid belief that the best development route was through conventional pyrometallurgical ore processing (heat) and the export of a concentrate to overseas smelters.

The new owner, London-based Kabanga Nickel, has adopted a different approach, preparing to use a hydrometallurgical refining process that significantly reduces power costs and pollution and leaves a residue perfect for backfilling the mine, as well as leading to domestically produced high-grade metal.

All of that is music to the ears of the Tanzania government, which has been urging miners to do more local value-adding and job-creating mineral processing - a key to Kabanga Nickel securing a binding framework development and ownership agreement with the government earlier this year, to be followed by a mining licence before the end of the year.

For Kabanga executive chairman, Keith Liddell, the development of a world-class nickel and cobalt mine will be more than justification of a three-year analysis, design and approvals process. It will also be a chance to again demonstrate a hydrometallurgical (acid based) technology leveraging from the Kell Process, which he developed more than 20 years ago.

Looking out over the Kabanga site

Kabanga will only require the first stage of Kell because it has little platinum, but the end result will be high-grade nickel refined in Tanzania to London Metal Exchange standards with an exceptionally low carbon footprint of less than half rival pyrometallurgical projects and 10% of Indonesia's nickel pig iron kilns.

The early interest of the big miners in Kabanga can be explained by the size and grade of the orebody, which has a resource estimate of 58 million tonnes assaying 2.62% nickel, 0.33% copper and 0.2% cobalt - a nickel equivalent of 3.21% or a copper equivalent 7.3%.

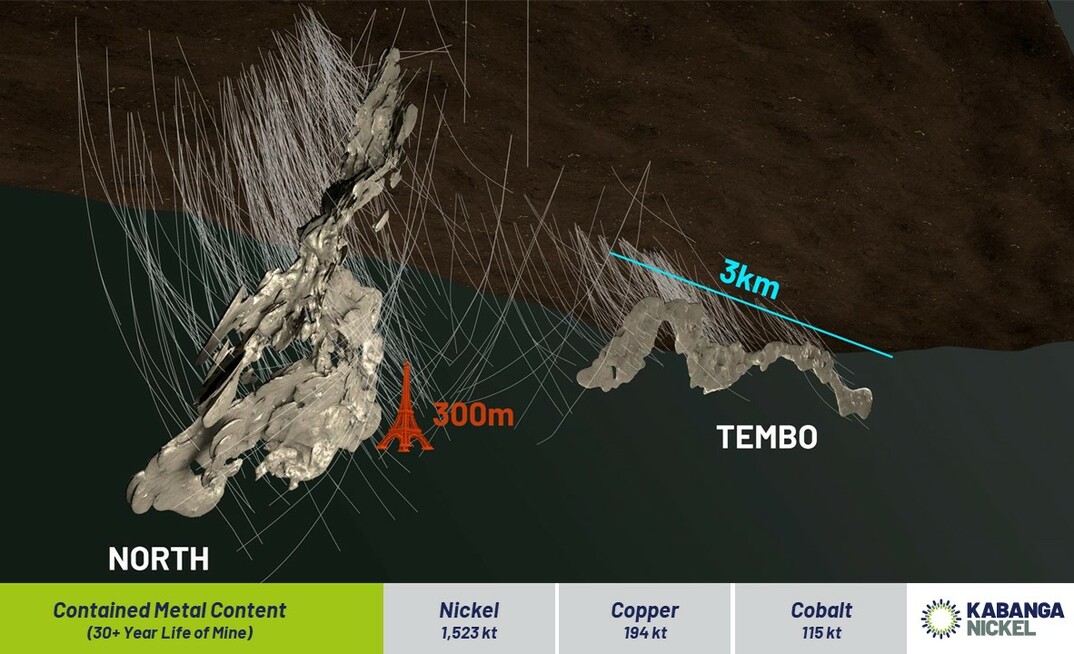

There are two main deposits earmarked for mining (North and Tembo), both starting between 80m and 100m from the surface with their ‘pluton' (chonolith) structure and composition similar to the magma intrusions found at some of the world's great nickel mines, including Norilsk in Russia and Voisey's Bay in Canada.

"The history of Kabanga dates back to the 1970s," Liddell said. "It's had this classic history of a lot of owners and a lot of quality work, including 600km of drilling, but it's never had its time.

"Factors which held Kabanga back included the price of nickel, location and a big company view that its ore could only be taken to the concentrate stage, which would be sent to a smelter offshore.

"We're going to do the concentration up to around 22% nickel at the mine before transporting it to the refinery, which will be built at an old gold mine with all of its established services, with finished metal sent in containers by rail to the port at Dar es Salaam for export."

The opportunity for Liddell to develop Kabanga came from a chance meeting with Barrick Gold chief executive, Mark Bristow, at the 2018 Indaba mining conference in Cape Town, where the question of the undeveloped nickel orebody came up in conversation.

At the time, Bristow was on a charge that led to the US$18 billion merger with Randgold Resources. A troublesome nickel-cobalt project was a distant blip on his radar screen, leading to his suggestion to Liddell: "Why don't you make a pitch for Kabanga at our executive committee meeting tomorrow."

What Liddell and his team found was a deeply analysed project that would fly in any other location, but was based on a process that did not deliver what the government wanted, local metal production.

The nickel price at the time had only just recovered from its 2017 low of $8,800/t; less than half its current $19,340/t and the electric vehicle (EV) rush was in its infancy.

Much has changed since Bristow and Liddell agreed to a deal consummated in a cash transaction at a price that remains private, but one which also has no trailing obligations such as a future royalty or offtake.

"It was a very clean deal between Barrick and my private investor group, which now owns Kabanga, clearing the way for our team to move in and pick up where Barrick and earlier owners left off," Liddell said.

The mine plan is conventional, except for their being two box cuts and two separate declines down to the North and Tembo orebodies; a dual approach which adds robustness to the mining side of the project.

"We'll spend the next 12 months restating Barrick's high-quality feasibility study and adding the metal refinery, so we'll have a complete mine-to-metal feasibility," Liddell said.

"An early start could be made on some site works, including the box cuts, and early-stage mining towards both orebodies."

The overall capital cost estimate for Kabanga (including a 20% contingency for overruns) is $1.3 billion. Funding talks are likely sometime next year, as well as a possible stock exchange listing, with London a potential destination at this stage.

After a two-year construction phase, commissioning is expected to start at the end of 2024, followed by a 12-month ramp up and life-of-mine annual production of 2.2 million tonnes of ore, yielding 40,000t of LME-grade refined nickel a year, plus 3,000t of cobalt.

Liddell is cautious with financial performance comments, but, at current nickel, copper and cobalt prices, Kabanga is likely to be a strong performer with nickel and cobalt consumers - especially as battery and EV makers are knocking on the executive chairman's door, keen to secure a reliable supply of environmentally clean (green) nickel.

But Liddell did provide a clue to future financial performance with this gem for banks and future investors to digest: "After you include the copper and cobalt by-products, the cost of producing the nickel is zero."